In HBO’s landmark 2014 crime drama, True Detective, two troubled detectives find themselves on the trail of a serial killer seemingly more interested in metaphysics than mere gratification. Like all good cop dramas, the pair are polar opposites, as much at war with each other as the killer they hunt.

Rust Cohle, played by Matthew McConaughey, is a jaded, nihilistic lone wolf. After the death of his daughter, he resigned himself from free will and self-determination. “We are things that labor under the illusion of having a self,” he intones. He is Arthur Schopenhauer with a Southern twang. Woody Harrelson’s Marty, on the other hand, has no time for the pessimistic morass of Cohle’s soliloquies, preferring to spend his nights away from his wife and kids drinking, fighting, and philandering.

As this odd couple tightens their grip on the killer’s henchman, they find themselves in a shoot-’em-up at a compound deep in the Louisiana swamps. After battling their way inside, Marty discovers two kidnapped and abused children – he murders their kidnapper without a second thought. In a flash-forward, Cohle reflects on the case: “Time is a flat circle,” he remarks. “Everything we’ve ever done or will do; we will do over and over and over again. And that little boy and girl, they’re gonna be in that room again… and again… and again – forever.”

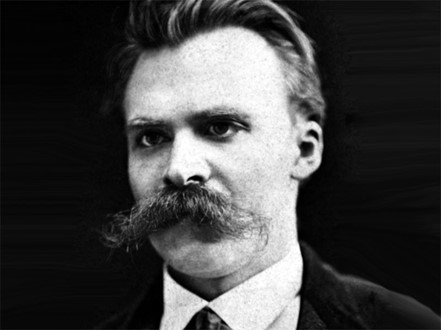

Drenched in the fiery petrol of Nietzsche’s philosophy, Cohle directly references the concept of Eternal Recurrence. In the penultimate section of The Gay Science, Nietzsche asks us to consider a thought experiment. What if, one night, a demon crept into your room and said to you that all your life, all its pain and joys, were to be repeated innumerable times?

“Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus? Or have you once experienced a tremendous moment when you would have answered him: ‘You are a god, and never have I heard anything more divine.”

In True Detective, this specter of infinite monotony is pessimism incarnate; for life is a horror show without remorse or salvation. Marty is doomed to be a philanderer, unable to stay his hand, to stay true to that which he loves, but forever to fail and give in to his basest desires. Cohle, meanwhile, is destined to live life alone – no escape. Whatever momentary happiness he found in the normalcy of his wife and daughter will inexorably turn to ash in his mouth.

To Nietzsche, however, such an interpretation is a perversion. Unlike Cohle, the German philosopher did not see man as an automaton. We are not “programmed,” nor are we a “tragic misstep,” as Cohle would have us believe. Rather, Eternal Recurrence causes us to pause and ask if we truly act with purpose. Would we be so callous or flippant with our time if we were destined to find ourselves here again? Eternal Recurrence is life-affirming, not denying.

Continuing in The Gay Science, we find one of Nietzsche’s most profound quotes:

“I want to learn more and more to see as beautiful what is necessary in things; then I shall be one of those who make things beautiful. Amor fati [love of fate]: let that be my love henceforth! I do not want to wage war against what is ugly. I do not want to accuse; I do not even want to accuse those who accuse. Looking away shall be my only negation. And all in all and on the whole: someday I wish to be only a Yes-sayer.”

The key line here is to see “what is necessary in things” – that life’s good moments only come after we’ve journeyed through the bad. And that pessimism is as much a choice as “looking away.” After all, to become – to escape one’s pessimism – is Nietzsche’s great hope. In fact, in his next book, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, the act of becoming is transmuted to all of humanity. Man is something to be overcome to herald the Übermensch – the higher man. The Last Man, in contrast, is he who cannot affirm earthly existence, who refuses to be overcome, and who dwells on life-suppressing norms and otherworldly illusions.

In the final moments of True Detective, the two detectives – now irrevocably bonded – share a short dialogue:

Rust Cohle: We didn’t get ’em all.

Marty Hart: Yeah, and we ain’t gonna get ’em all. That ain’t what kind of world it is. But we got ours.

Rust Cohle: I’m not supposed to be here.

Marty Hart: Yeah… well, I’ll come back by tomorrow, buddy.

Rust Cohle: Why?

Marty Hart: Don’t ever change, man.

But Cohle has changed. His final line, “Once there was only dark. If you ask me, the light’s winning,” suggests a true change of heart – a refutation of pessimism. How do we reconcile these two aspects: Not to change and yet to become something more? Nietzsche once again holds the answer: “Become Who You Are,” he implores. In a task of Sisyphean heroism, we must become who we are destined to be and to love our fate. And if we don’t manage it? Well, there’s always tomorrow, buddy.

Categories: Philosophy

“Become what you are” is the ultimate goal for a person seeking enlightenment. Overcoming pessimism is a victory of light over darkness.

LikeLike

This has made me accept that I’m responsible for my own change, for my tomorrow depends on what I’m doing to put some light to it today.

LikeLike